The Humanoid Dream: From El-Cezerî’s Automata to Boston Dynamics’ Atlas

- Hevi Akademi

- May 27, 2025

- 4 min read

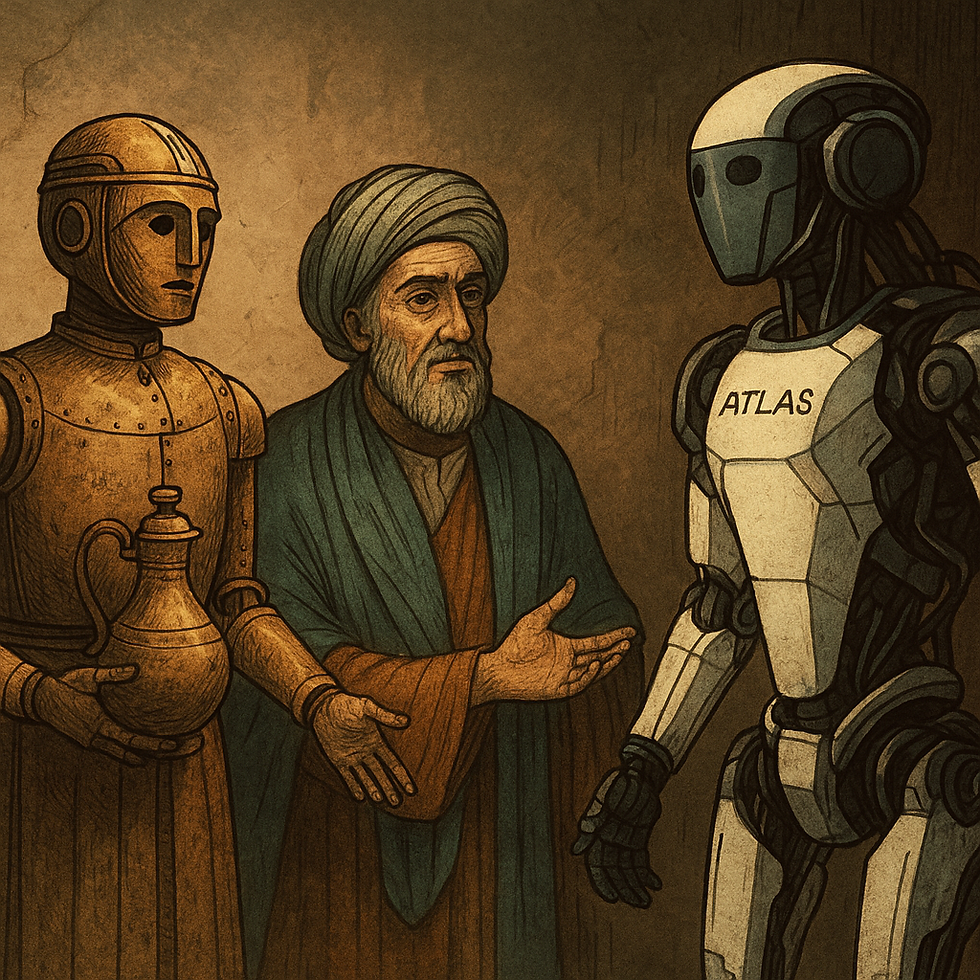

In the early 13th century, on the banks of the Tigris in the ancient Kurdish city of Cizre, a man quietly redefined the boundaries between nature, mechanics, and divine imagination. His name was El-Cezerî, a polymath, engineer, and visionary of a kind the world would not see again for centuries. Within the stone walls of the Artuqid palace where he served as chief engineer, El-Cezerî authored a book that would become one of the greatest scientific treatises of the medieval Islamic world: Kitab al-Hiyal — The Book of Ingenious Devices.

What lay within its pages would appear, at first glance, like something between artistry and sorcery. But as the diagrams unfolded, revealing hidden mechanisms of gears, floats, valves, and cams, a new realization dawned: these were not toys. They were automata — self-operating machines, many of them humanoid in appearance, capable of movement, speech, and even programmed behavior. Among them, the famed robotic servant, who could pour water for ablution, hand over a towel, and bow respectfully after the task was done. Here stood, in metal and wood, one of history’s first programmable humanoid machines — not in Paris, not in Rome, but in Kurdistan, in the court of Cizre.

Though centuries would pass before the term "robot" was ever coined (by Karel Čapek in 1921), and longer still before silicon chips would replace gravity-fed levers, the essence of the humanoid dream had already been articulated: a machine that mimicked the human form and served human needs, not just in function but in expression.

Yet, the brilliance of El-Cezerî — like much of the Islamic Golden Age — was buried beneath colonial dismissals and Eurocentric chronologies. His influence, though translated and studied in parts of Europe, rarely received due credit. The Renaissance came and went. Leonardo da Vinci sketched his own mechanical knight. European clockmakers produced elaborate automata that wrote letters and played flutes. But none rivaled the elegance, utility, and complexity of the devices in El-Cezerî’s book.

It wasn’t until the rise of the Industrial Revolution that humanity once again touched the gears of mechanical autonomy. But this time, the intent had changed. Factories required repetitive precision, not humanoid grace. The robot became a metal arm — rigid, blind, tireless. In 1961, Unimate, the first industrial robot, began work at a General Motors plant. It did not look human. It was never meant to.

Still, the desire to recreate human movement never disappeared — it merely evolved alongside computing. As microprocessors shrank and algorithms grew smarter, a new age dawned. In Japan, Honda launched ASIMO, a child-sized humanoid that could walk, climb stairs, and greet guests. Sony’s AIBO gave a pet form to mechanical intelligence. And in America, in a lab blending military contracts with cutting-edge robotics, something remarkable began to take shape.

Atlas, a humanoid robot developed by Boston Dynamics, first emerged as a clunky machine built for rescue operations. But what followed in the next decade astonished even the skeptics. By 2023, Atlas could run, jump, lift weights, manipulate tools, and — most famously — dance. Not stumble, not approximate, but truly dance — with rhythm, balance, and astonishing agility.

The videos went viral. A two-legged, headless robot moved like a trained performer, executing synchronized steps to “Do You Love Me?” with more precision than many humans. The public laughed, gasped, and debated: was this impressive, creepy, or dangerous?

Technically, Atlas embodies the cutting edge of robotics. With 28 hydraulic joints, real-time motion planning, computer vision, and AI-based control systems, it represents the culmination of centuries of engineering evolution. Yet behind its smooth flips and somersaults lies the DNA of every robotic thinker before it — and perhaps, the shadow of a Kurdish engineer who once made his machines bow.

What makes this story more than a timeline of machines is the poetic arc it follows. El-Cezerî created machines to reflect human service and beauty — not to replace labor but to elevate experience. His automata were theatrical, ceremonial, and symbolic. Similarly, Atlas is not only an experiment in motion but a performance of intelligence. When it dances, we are reminded not of labor, but of play — not of efficiency, but of elegance.

As we gaze into a future populated by humanoids that can speak, emote, create art, or care for the elderly, we must remember that the future of robotics is also a history — one that began not with silicon, but with copper pipes and wooden gears in the ancient courts of Kurdistan.

In every leap Atlas takes, and every digit it flexes, we may hear the quiet hum of a water-powered servant from Cizre, whispering through the centuries, “I was here first.”

---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Footnote:

This article is part of Hêvî Akademî's “Zêrekîya Nû” series, tracing the evolution of intelligence — human, mechanical, and artificial — from Mesopotamia to Mars.

Comments